In the Land of Cockaigne - Robert Aberdain, Bobby Baker, Caroline Wong, Lindsey Mendick, Paloma Proudfoot, Olivia Sterling

March 5, 2022 - April 9, 2022

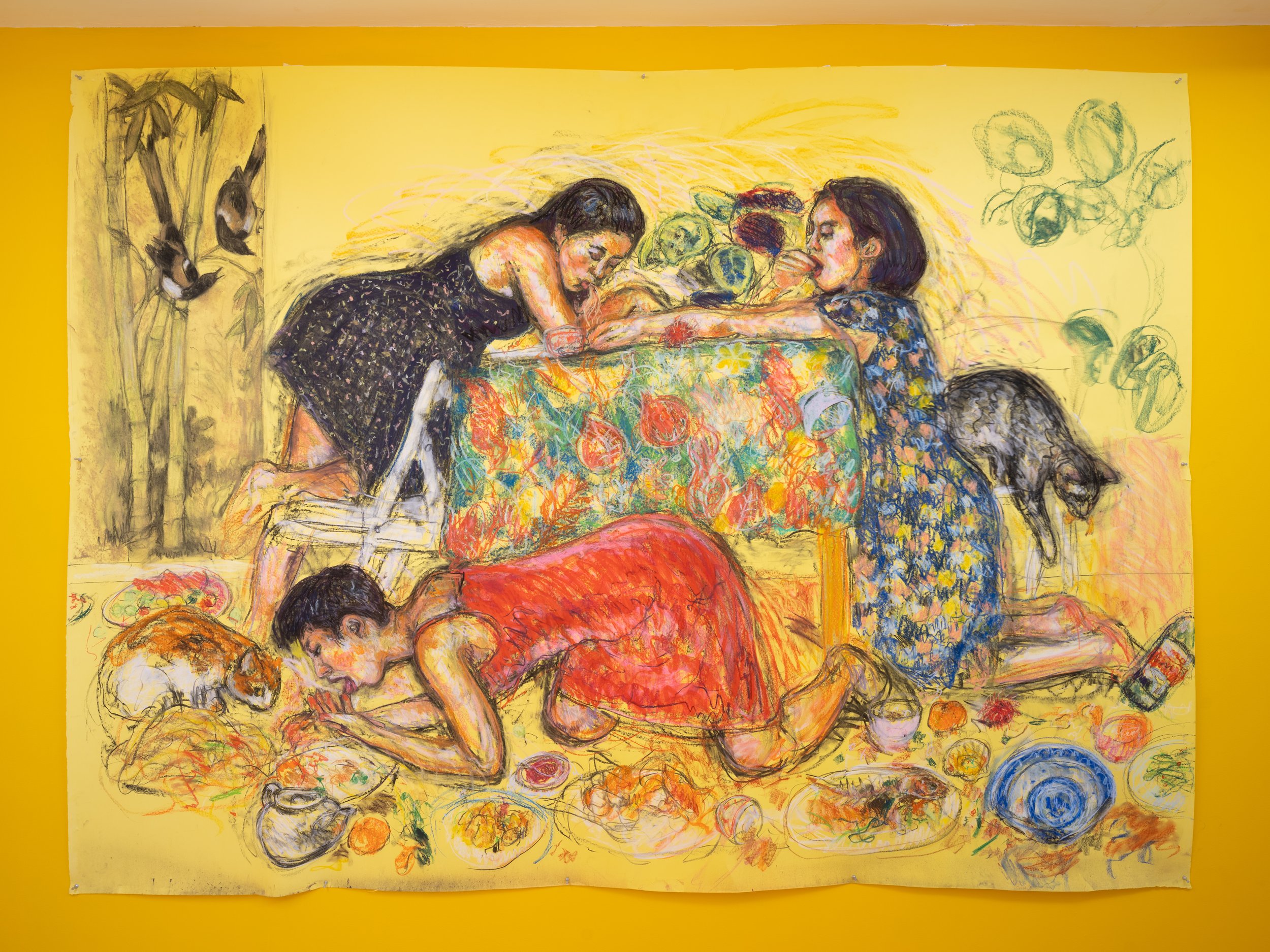

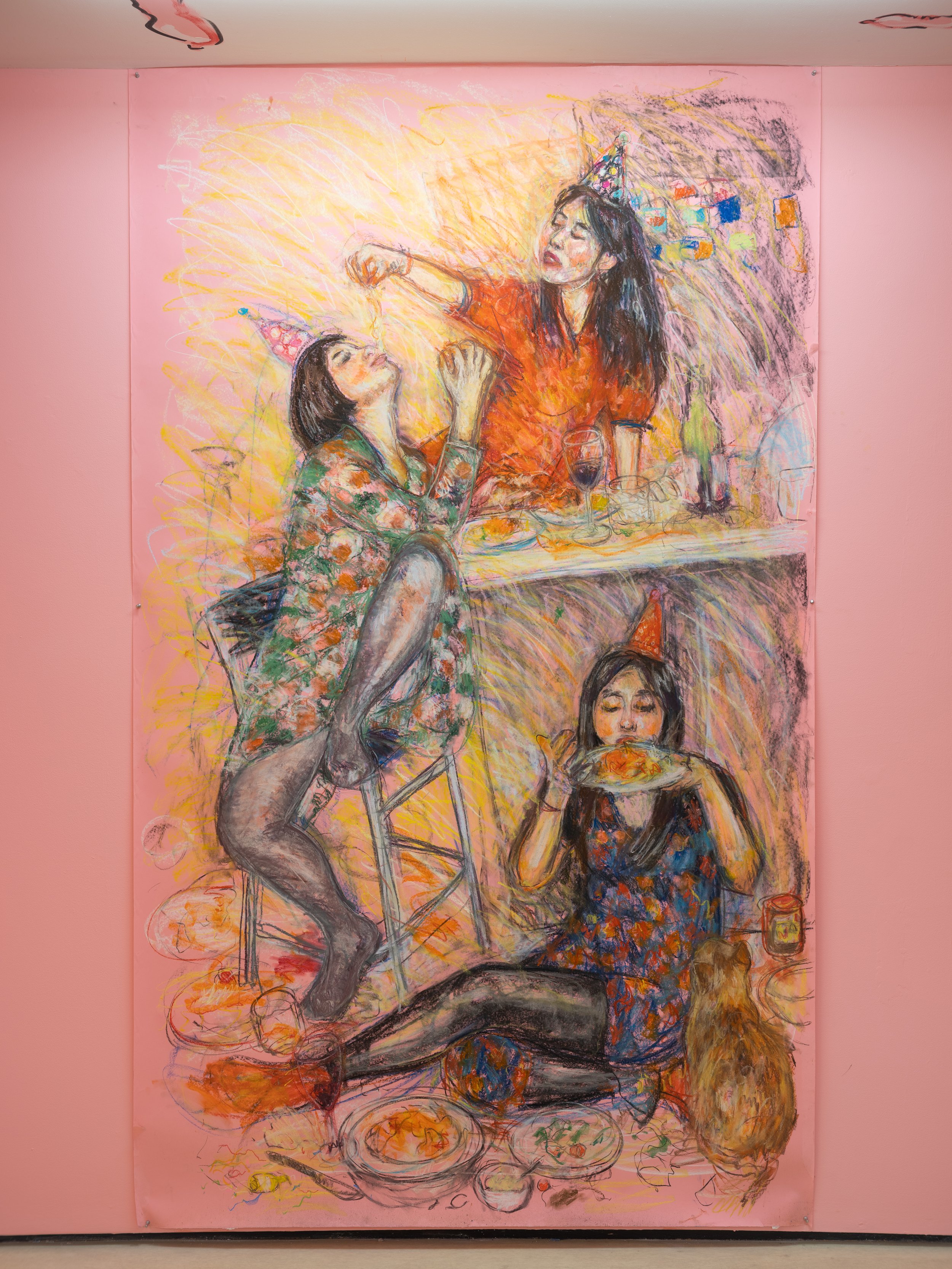

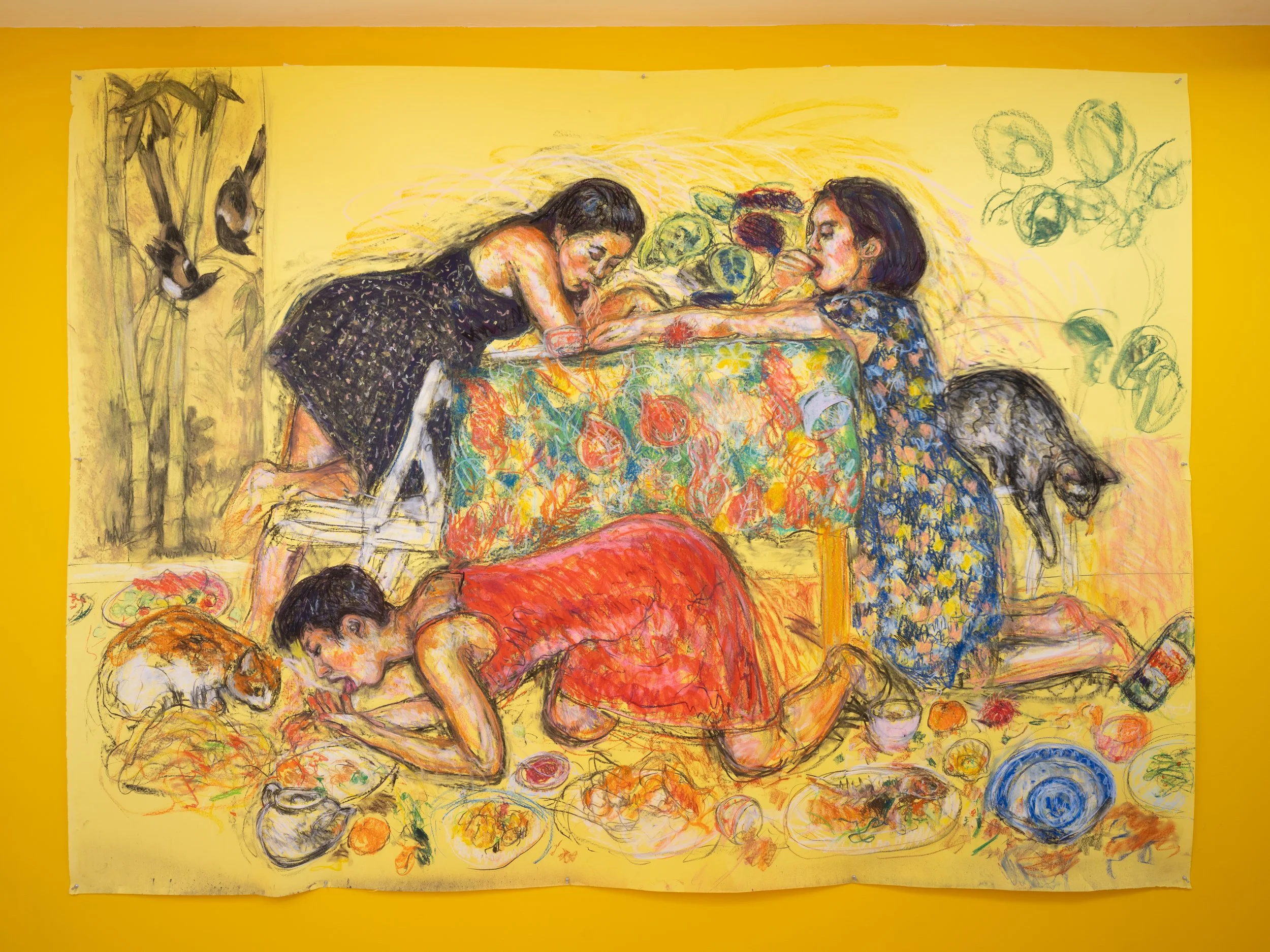

New Year’s Eve by Caroline Wong, 2022

In the land of Cockaigne

“...vibrant with excess that giddy farmers hail

by tossing animals, large animals,

into the air to be carried away

on the winds of exuberance

to the four corners of the globe

where the romping gods

bear so many attributes

they're a bundle of incongruities

and no one takes them seriously

not even their beaming angels

who parachute drunkenly down to the shore

distracting the dogs let loose on cormorants

that ate so much they can't fly…”

Just imagine…the imaginary land of extreme luxury and ease, where physical comforts and pleasures are always immediately at hand. Just imagine…imagine a world where there is an unlimited stream of food and wine. Imagine the rivers of wine, houses built of cake and barley sugar, streets paved with pastry, and shops that spontaneously give goods to everyone. A never-ending supply of food, abundance, pleasure, and consumption. Cockaigne has been referenced a number of times, especially prominently in medieval European lore, also depicted by Breugel’s seminal painting The Land of Cockaigne (1567) where he vividly illustrates the direct connection between human lethargy and a tendency towards vice. Gluttony takes over in Cockaigne; gluttony that permeates all social classes.

The medieval satirical poem The Land of Cockaigne was written in the early to mid-fourteenth century by an unknown writer. It was later translated into contemporary English. The Land of Cockaigne begins lightheartedly but becomes more caustic, then vicious and unbearable as a result. In Cockaigne “...food and drink are had without worry, trouble or toil. The meat is a choice and the drink is clear at every meal: noon, afternoon and evening. I swear this land has no peer under heaven or on earth for such joy and bliss. There are many sweet sights; it is always day, never night. There is no quarreling or strife, no death but ever life. There is no lack of food or clothing, and no man or woman is ever worth.”

The group exhibition titled In the Land of Cockaigne at Quench presents the works of artists Robert Aberdein, Bobby Baker, Lindsey Mendick, Paloma Proudfoot, Olivia Sterling, and Caroline Wong. Each artist explores the themes of abundance, the right to pleasure, the absurdity associated with the consumption of food, domesticity, race, and revulsion in the context of food politics. In the last two years, food waste, food shortages, and inequalities have come to light, especially in the context of the post Covid-19 pandemic climate. In the Land of Cockaigne takes these issues a step further and unleashes our prohibited desires and our collective hunger for more. The colours of the gallery walls depict one’s inner cravings; light pink for ham, mustard yellow for dressing, and burgundy red for wine.

Although Margate-based artist Robert Aberdein’s sculptures come from the classical tradition, the texture and forms in his raw stoneware clay, phallic-like works explore themes around vulnerability, weakness, and fragility. Playfully responding to the land of “Cock-aigne”, Aberdein creates his own interpretation. Somewhat seductive and disturbing at once, the sculptures invite the viewers in. Rather than pursuing her artistic practice as a rarefied activity, Bobby Baker has persistently exposed the undervalued and stigmatised aspects of women’s daily lives over a 50-year career that has included performance, drawing, and installation. Shown at Quench for the first time since its original broadcast by the BBC 25 years ago, Baker presents her 9 minute film Spitting Mad. Using her mouth to apply a variety of foodstuffs onto white rectangular cloths, we see Baker create a series of images while providing commentary on the artistic processes and decisions being made. Both through painting and performance, the sequence of actions are delivered with Baker’s trademark humour and wit to vulgar and shocking effect. Lindsey Mendick’s humorously decadent and elaborate ceramic vases with tentacles, oozing tongues, and phallic protrusions enable the viewer to explore their personal history but also indulge in their exorbitance. Both desirable and tactile, these ceramic sculptures seduce the viewer and invite them into the Land of Cockaigne.

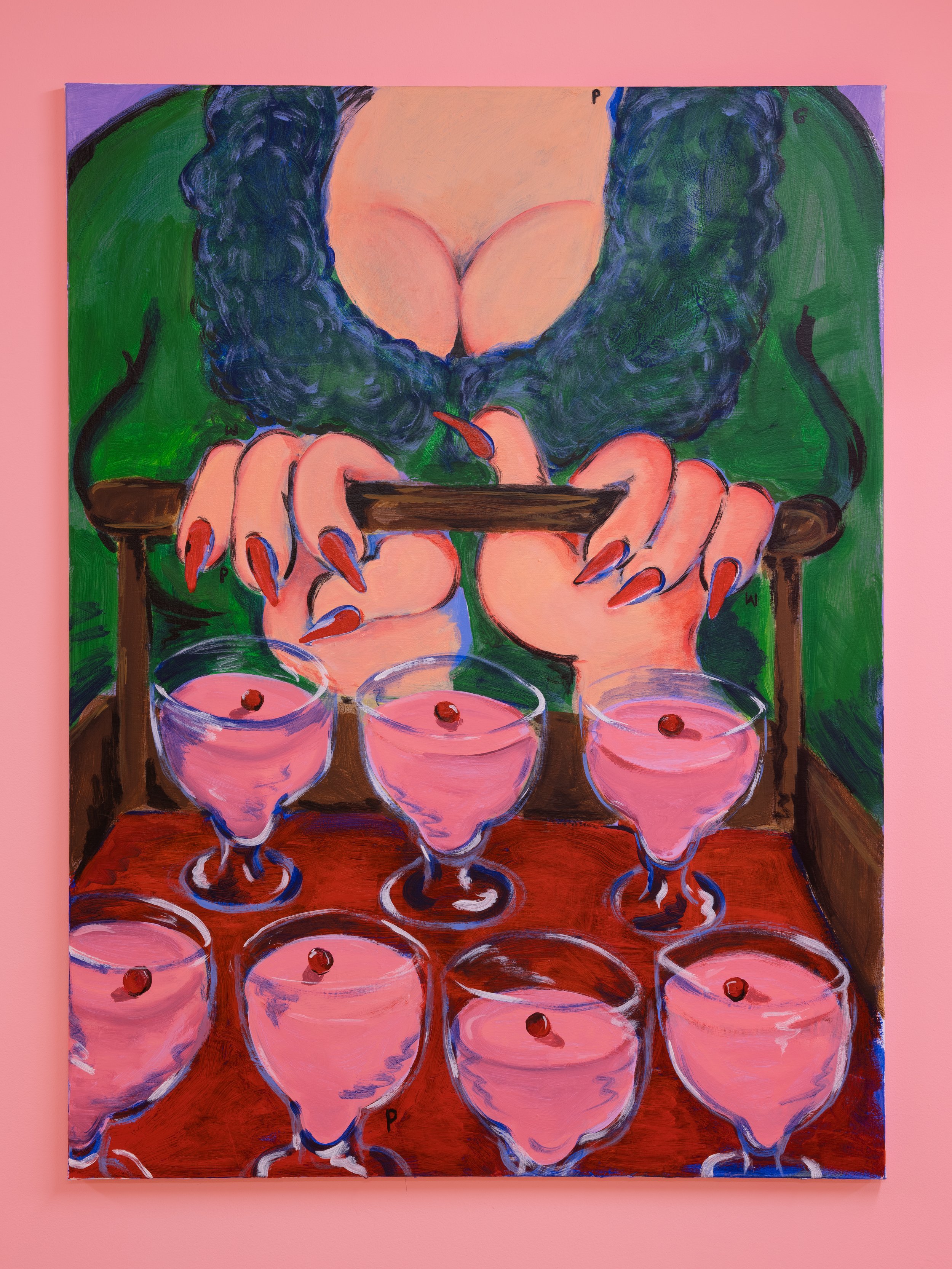

Textile and organic matter, such as clay, are common materials appearing in Paloma Proudfoot’s artistic practice. The works titled Ambrosia I, II, and III are part of a series of pieces where the artist explores how anatomical scientific representations of the body could merge with a more emotional language. The web-like delineation of each organ and section is apparent in these fragile-looking ceramics. Proudfoot builds her own metaphorical language to describe how the stomach reacts to emotional turmoil – a constriction, tightening, often expressed as ‘my stomach is in knots’ – using the tightened belt weaving into arterial knots as a representation of this compression. Both intricate but also quirky, Paloma’s clay works respond to the exhibition in the most mysterious and unusual ways. Olivia Sterling uses painting to address questions of blackness and whiteness in twenty-first century Britain. She achieves this through scenes of colourful mayhem with a nostalgic twist and signature ‘slapstick’ style with a subtle critique of race and inequality. Never showing the face, the hands gesture at skin colour or connotations to that person’s character. Sterling creates playful, stereotypical scenarios where she often tries to make fun of them – exposing the innate absurdity that comes with visual-based discriminations. Breaking the boundaries of the ideology and representation of women, Caroline Wong’s drawings recollect the pleasures of eating and drinking with friends, celebrating conviviality whilst also critiquing sexism in East Asian societies. In her ongoing series Hungry Women of rapaciously drawn images of gluttonous women, Wong explores the relationship between creation and consumption - the escapist pleasure of both, the potential to overindulge, the return to a younger, less inhibited self. Colours, textures, and materials become flavours or ingredients in her quest for delicious images. The use of oil pastel in Wong’s paintings is reminiscent of butter, grease, and cream.

Tactility, sensuousness, and pleasure take over the exhibition.

I am now hungry.

I am famished.

I want more.

Food has always been a connector, a universal language, an essential part of our lives - it has also been used as a metaphor in many different contexts. Masterfully, Futurists staged performance dinners, inspiring many others to this day. Within Surrealism, artists such as Méret Oppenheim, René Magritte, and the founder of the movement, Salvador Dali, often used representations of food to interrogate the subconscious mind. In the contemporary art context, food politics and social practices have become closely intertwined. Especially in the context of the catastrophic impact mankind has inflicted on the natural environment, food scarcity and food waste have become quite precarious. The beginning of 2020 and the Covid-19 crisis heightened all these problems to a new level but also created awareness. In the Land of Cockaigne not only questions and resurfaces these issues but responds to them in a somewhat playful, nonsensical, and absurd way.

Curatorial text written by Huma Kabakci

Robert Aberdein

Robert Aberdein lives and works in Margate. Robert Aberdein's sculptures come from the classical tradition, however, their intent is not to portray strength, beauty, and immortality - rather vulnerability, weakness, and fragility.

Sculpting predominantly in raw grogged stoneware clay, and having graduated from the Norwich School of Art, Aberdein drags his forms out of this earthy matter, clawing, moulding, and forming figures direct from his imagination and the world around him.

Bobby Baker

Bobby Baker (b. 1950, Kent) lives and works in London. She graduated from Painting at St. Martins School of Art (1972) and holds an Honorary Doctorate from Queen Mary University London. Baker’s acclaimed intersectional feminist practice includes performance, drawing, and installation, and persistently exposes the undervalued and stigmatised aspects of women’s daily lives, this is exemplified by pioneering works such as Drawing on a Mother’s Experience (1988), Kitchen Show (1991), The Diary Drawings (1997–2008) and more recently Great and Tiny War (2018). Since 1995 she has led the organisation Daily Life Ltd. to make art that explores and celebrates everyday life and human behaviour and collaborate with like-minded artists and organisations across the arts, health, and disability sectors.

Huma Kabakci

Huma Kabakcı (b. 1990, London) is an independent curator, and founding director of Open Space, living and working between London and Istanbul. Kabakcı has extensive experience in fundraising and has worked at the Drawing Room, London (2021-22) as a Development Manager. She studied at the London College of Communication and completed an MA in Curating Contemporary Art at the Royal College of Art. Kabakcı completed a curatorial fellowship at the 2018 Liverpool Biennial, supported by ICF (International Curators Forum). Kabakcı’s curatorial interest lies in creating immersive experiences and a wider dialogue in collaboration with multidisciplinary practitioners. She is also interested in theories and topics around diaspora, collective memory, hospitality, and food politics.

Lindsey Mendick

Lindsey Mendick (b. 1987) lives and works in Margate, UK. She received her BA from Sheffield Hallam University (2012) and has an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art (2017).

Mendick’s practice is hinged on her skilled work in ceramics, which she is drawn to for their tactile nature and desire to be manipulated by the maker. She also embraces banner painting, sewing, metalwork, furniture making, and sound within her autobiographical practice. By playfully combining low culture iconography and high culture methods of construction, Mendick creates humorously decadent and elaborate installations that enable the viewer to explore their personal history in a cathartic fashion.

Awards include the Henry Moore Foundation Artist Award (2020); the Alexandra Reinhardt Memorial Award (2018); selection for Jerwood Survey (2019); and selection for the Future Generations Art Prize (2020).

Paloma Proudfoot

Paloma Proudfoot (b. 1992, London) is an artist living and working in London. She received a BA in Sculpture from the Edinburgh College of Art and an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art.

Proudfoot uses sculpture, clothes-making, text and performance to weave together personal experience, historical references and contemporary cultural observations. Seeking articulation for amorphous feelings such as shame, grief and strength, she pushes the metaphorical and narrative potential of materials. As well as her solo practice Proudfoot works with different collaborators including artist and choreographer Aniela Piasecka; the performance group ‘Stasis’; and Lindsey Mendick as ‘Proudick’.

Olivia Sterling

Olivia Sterling (b. 1996, Peterborough) lives and works in London. She received a BA in Fine Art from the University of Derby (2018) and an MA in Painting from the Royal College of Art (2020).

Sterling uses painting to address questions of blackness and whiteness in 21st century Britain. Her work presents scenes of colourful mayhem with a nostalgic twist and a signature ‘slapstick’ style, combining joyous celebration with a subtle critique of racialised ways of seeing. Blending pointed references like this into her depiction of ordinary scenes and subjects, Sterling’s work reflects on how we are confronted by racialized discourse everywhere in the everyday. Even happy or anodyne spaces are encoded with structures of othering and difference; every object and every skin tone is assigned its place in a drama that continues beyond the edges of the canvas.

Caroline Wong

Caroline Wong (b. 1986, Malaysia) lives and works in London. She received a Diploma in Contemporary Portraiture from The Art Academy (2018) and an MA in Fine Art from City and Guilds Art School (2021).

For Wong, the act of creating, much like eating, is sensuous and consuming. Whether found, recovered, or taken from life models, images of women are her work's foundation. As the connecting tissue of her practice is a subversive response to traditional, restricted representations of East Asian women, she looks for a kind of confidence, a rebellion, an emotional voluptuousness in her subjects which translates to the way she works. Wong luxuriates in the epicurean side of herself, producing excitable, expressive marks and heated, joyful colour driven by a hedonistic desire for fun, producing work that is a jubilant pushback against tradition.